Respond to Deterioration

Responding to deterioration in people with dementia ensures:

- Signs of deterioration are identified early and addressed.

- Timely management of symptoms.

- Complications may be prevented.

What does deterioration in people with dementia look like?

Deterioration refers to signs that the health of the person with dementia is declining. In late dementia, symptoms significantly worsen, impacting memory, communication, and physical abilities. Recognising deterioration can be challenging due to the gradual progression of the disease. This can sometimes make it difficult to identify when palliative care is needed.

Typical Illness Trajectories

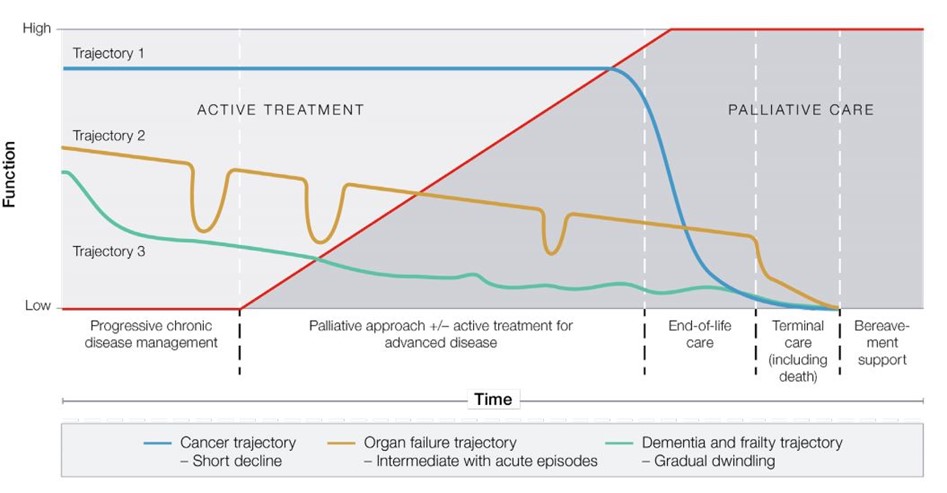

People will experience different illness trajectories depending on the primary diagnosis and presence of other diseases (co-morbidities). Three typical illness trajectories for people with progressive chronic illness are described and illustrated in the figure below. [1, 2]

-

Trajectory 1

-

Trajectory 2

-

Trajectory 3

Trajectory 1: Cancer (short decline)

For these individuals there is a steady progression with a slight decline in physical health over months to years. Evident decline occurs in the end-of-life phase, which includes increasing symptoms, rapid decline in weight and functional status in the last weeks or months of life. [1, 2]

Trajectory 2: Organ failure (intermediate with acute episodes)

These individuals have non-malignant, life-limiting illness with organ failure. There is decline in function over years with long-term limitations, often life-threatening episodes requiring hospital treatment, followed by further deterioration. During this trajectory there may be episodes of improvement only for function to decline again. Death can seem sudden and may occur at any time along the gradual decline in function. [1, 2]

Trajectory 3: Frailty or dementia (gradual dwindling)

People living with dementia have a long and varied disease progression for up to 6-8 years. This includes early impairment of memory, reduced decision-making and communication capacity. Frailty is a syndrome of general physiological decline that often lacks a specific diagnosis. In this trajectory, the last year of life is characterised by a steady slow decline in overall function. If dementia and frailty occur together decline is more rapid. [1, 2] The relationship between frailty and dementia highlights the need for early intervention and monitoring both frality and cognitive function. [3]

Typical illness trajectories and palliative care phases towards the end of life

Reproduced with permission from: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. RACGP aged care clinical guide (Silver Book). 5th edition. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2019, 2020. Available at www.racgp.org.au/silverbook

-

Signs of deterioration

-

Identify the cause of deterioration

-

Tools to identify deterioration

Ask a family member or carer if there has been a change in the person's condition.

The person in late-stage dementia may:

- lose recognition of familiar people

- gradually lose the ability to perform daily tasks

- experience incontinence

- be affected by other conditions like stroke or arthritis

- struggle to understand conversations and surroundings

- lose the ability to talk

- call out occasionally

- forget how to eat or drink, and have trouble swallowing

- experience weight loss

- become bed or chairfast. [4]

Despite these challenges, the person with dementia can continue to show emotions and sensory experiences.

For people with dementia, it is necessary to identify and respond appropriately to deterioration, which may be from their primary diagnosis or because of other disease or events.

It is important to distinguish between deterioration that is due to treatable versus untreatable causes. Treatable causes are situations such as an acute or medical emergency that may warrant review and treatment. For instance, a urinary tract infection can be treated. Untreatable or irreversible causes could be due to disease progression.

Good clinical assessment and consultation with other team members (e.g. GP, Nurse Practitioner, Neurologist, Psychogeriatrician) is critical. If needed, external experts, such as specialist palliative care or dementia advisory services should be contacted for assistance. Family and carers should also be contacted when a person is deteriorating.

A sudden deterioration, such as acute confusion, may indicate delirium characterised by inattention and disturbance in cognition that develops over a short period of time and tends to fluctuate. Delirium is potentially preventable and treatable. However, major barriers, including under-recognition, are an issue. [5] It is advised to use a recognised tool, such as the 4AT (273kb pdf).

- The Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICTTM) (184kb pdf) or SPICT-4ALLTM (186kb pdf) can be used during routine care evaluations and following an unplanned hospitalisation. It may indicate a change in an older person’s condition that warrants a review of care needs.

- The SPICTTM includes specific clinical indicators for dementia/frailty:

- Unable to dress, walk or eat without help.

- Eating and drinking less, difficulty with swallowing.

- Urinary and faecal incontinence.

- Not able to communicate by speaking; little social interaction.

- Frequent falls, fractured femur.

- Recurrent febrile episodes or infections, aspiration pneumonia.

- Visit the SPICTTM website for user guidelines and further information.

- The Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool (481kb pdf) can be used by care workers to spot signs of deterioration in people. The tool can be used in situations of increased concerns when team members notice that something isn’t quite right.

- Other clinical tools are available for symptom assesment in the section on Assess Palliative Care Needs of the ELDAC Dementia Toolkit.